|

Mexican Wolf Biological Information |

||||

|

Wild populations of Mexican gray wolves were exterminated before they were extensively studied, therefore much of their natural history remains to be learned. The average Mexican gray wolf weighs 50-80 lb (25.8-36.24 kg), is 4.5 to 5.5 ft (135-165 cm) in total length (nose to tip of tail), stands 28-32 in (70-80 cm) at the shoulder and has a richly colored coat of buff, gray, rust, and black. They breed from late January through early March, and have a gestation of 63 days with an average litter size of 4-5 pups. Wolves have complex social behaviors, living in family groups called "packs", the structure of which is maintained by communication through vocalizations, body postures, and scent marking. Wolves play an important role in the ecosystem that is not filled by other predators. Like all gray wolves, lobos evolved as a predator of large hoofed mammals. Their tightly organized group structure enables them to work cooperatively to bring down prey much larger than themselves. However, because the primary prey of the Mexican gray (deer, elk, and small mammals) is smaller than the moose and caribou hunted by northern wolves, wolf pack sizes were probably smaller as well. A typical pack may have been five to six animals consisting of an adult pair and their offspring, with a territory encompassing up to several hundred square miles. |

||||

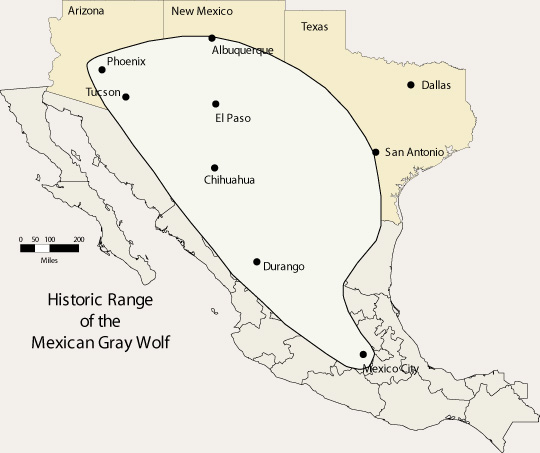

Mexican gray wolves were found in a variety of southwestern habitats; however, they were not low desert dwellers. They preferred mountain woodlands, probably because of the favorable combination of cover, water, and available prey. The lobo inhabited wooded foothills, mountains, and riparian corridors from central Mexico through southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico and western Texas.

Reasons for Decline |

|

|||

In the early 1900s high cattle stocking rates coupled with over hunting of deer and elk by humans, resulted in many wolves preying on livestock. This led to intensive efforts to eradicate wolves in the United States. Wolves were shot, trapped, and poisoned by both private individuals and government agents. By the mid-1900s, Mexican gray wolves had been effectively eliminated from the United States, and Mexican populations were severely reduced. Over the next 20 years dispersing wolves from Mexico were occasionally caught and killed in the U.S. There have been no confirmed reports of naturally occurring Mexican gray wolves in the U.S. since 1970, and no confirmed reports in Mexico since 1980, however, unconfirmed reports continue today. |

||||

Population Management With breeding being such an important part of this recovery program, population management plays a critical role in the species success. Read more Founders The founders, or initial members, of a population are the largest factor in determining the characteristics and overall health of a population. The fewer the founders, the more challenging it is to successfully recover the population. The mexican wolf population only had seven founder, much fewer than most other recovery programs have had. Read more Genetics Although persisting as a subject of often intense debate within many realms of the conservation community, the management of animal populations in captivity remains an important and often vital component of an endangered species management strategy. The final goal of most captive management programs includes the reintroduction of healthy captive-born individuals to wild habitats that best suit their biological needs and are as free as possible from human interference. To help achieve this goal, zoo population managers work hard to secure the health of these individuals – not only in terms of their physical well-being, but also with regards to their very genetic make-up. Read more Recovery In order for the studbook keeper and the captive community that house Mexican gray wolves to be successful with their charge of preserving an endangered species, they need a plan. Read more |

||||